Things to Do in Linz & Upper Austria: 4-Day Itinerary

Linz has a reputation problem, and it knows it. Forever standing in the cultural shadow of Salzburg, this Danube-side city quietly decided not to compete, but to outthink. While Salzburg perfected powdered wigs and operatic drama, Linz leaned into algorithms, contemporary art and a slightly rebellious creative streak. And that’s exactly where its charm lives.

Upper Austria follows the same rulebook but then scribbles all over the margins. One moment it’s imperial and polished, the next it’s raw, reflective and unexpectedly bold. Baroque monasteries double as scientific powerhouses. Lakes behave like mirrors with commitment issues. Towns like Bad Ischl and Steyr don’t perform for applause; they simply exist with the confidence of places that once shaped empires and still know it. But what makes Linz and Upper Austria quietly magnetic is their refusal to be obvious. The culture runs deep but never tries too hard. History is present, but it doesn’t lecture. Even the landscapes play it cool. Alpine, yes, but thoughtful; scenic, but never screaming for a postcard. There’s an elegance here that feels earned, not staged. Salzburg may take a bow. Linz prefers a knowing smirk.

And then there’s the rhythm. Days here unfold like a well-edited story with sharp opening ideas, layered middle acts, and a finish that lands without overexplaining. It’s a place that rewards curiosity, lateral thinking, and travellers who enjoy connecting dots rather than ticking boxes. If Salzburg is a polished symphony, Linz and Upper Austria are a perfectly timed remix. They’re unexpected, confident and slightly addictive.

To make sense of it all (and keep the plot tight), we’ve prepared a thoughtfully paced, high-end 4-day itinerary through Linz and Upper Austria, designed to follow the region’s logic not the brochure’s.

Day 1 - Linz

Morning: Hauptplatz Linz

The tour opens where Linz has always flexed its quiet confidence: Hauptplatz, one of Austria’s largest main squares.

Since the 13th century, this expansive plaza has been the setting for imperial announcements, market trading, political shifts and the everyday theatre of Danube life. Baroque façades line the square with a kind of effortless symmetry, while the Trinity Column at its center, raised after the plague and Ottoman wars, stands as both a monument and a reminder that Linz has survived, adapted, and kept moving forward. This isn’t a square that begs for attention; it assumes it.

For travelers who like their history with polish, Hauptplatz shines brightest through private guided walking tours of Linz’s Old Town which are often led by art historians or architecture specialists who unpack the symbolism behind the façades and monuments.

Landhaus

Power walks well here. From Hauptplatz, it’s an easy three to five-minute stroll through the Old Town streets. No rush. The transition from open square to enclosed courtyard is part of the point.

This is where Upper Austria has been making decisions since the Renaissance. Landhaus Linz dates back to the 16th century and remains the seat of the provincial government today, which already says a lot about its staying power. The architecture leans Italianate with arcaded courtyards, clean proportions and a calm confidence that does not need ornament overload to impress. At the center stands the Kepler Fountain, a subtle nod to Johannes Kepler who lived and worked in Linz while shaping modern astronomy. Politics, science and design all collide here, politely and on schedule. This spot is also often included in private Old Town and architecture-focused walking tours. You might want to join one when you visit this place.

Church of St. Martin

Old stones. Short walks. Big timelines. From Landhaus Linz, the route shifts uphill and slightly inward. A five-minute walk leads to a place that predates most of the city around it.

The Church of St. Martin is one of the oldest surviving churches in Austria, with roots tracing back to the 8th century. That alone earns attention. Built atop Roman foundations, Martinskirche carries layers of early Christianity, Carolingian influence and medieval adaptation all in one compact structure. The exterior keeps things simple. The interior leans contemplative. This was never meant to impress through scale but through continuity. Centuries passed. The church stayed. That quiet endurance is the flex.

Afternoon: Lentos Kunstmuseum

The city suddenly remembers it has a river to show off. A gentle downhill wander toward the Danube takes about ten unhurried minutes, and the atmosphere shifts from medieval hush to contemporary confidence.

Lentos Kunstmuseum anchors the riverbank with a glass façade that feels both precise and playful. Opened in 2003, this architectural statement announced Linz’s arrival as a serious player in modern and contemporary art. Inside, the collection moves between classical modernism and bold contemporary works, with notable ties to Klimt-era Vienna and postwar Austrian movements. Natural light floods the galleries during the day, while evenings turn the building into a glowing cultural beacon along the Danube. Art here does not sit still. It converses.

Those craving context can join public guided tours, thoughtfully led by the museum’s art education team. These tours offer a clear entry point into the permanent collection and current exhibitions and take place every Thursday at 6 pm and every Sunday at 4 pm, conducted in German. For a deeper intellectual stretch, art talks appear at irregular intervals and are hosted by curators, researchers and invited experts who pull back the curtain on curatorial decisions and exhibition themes.

Donaulände

Now the city exhales, architecture loosens its tie and the river steps in as the main character. The route naturally spills outward until stone streets flatten into open sky and water and the Danube quietly takes over.

Donaulände is Linz’s long, elegant handshake with the river. Once a working trade corridor, this stretch of promenade has evolved into a cultural and urban axis where the historic city meets contemporary design. Museums, public art and performance spaces line the banks, turning what could have been a simple riverside walk into a curated experience of movement and pause. The Danube has shaped Linz for centuries. Here, that relationship becomes visible, walkable and refreshingly relaxed.

There’s no other way to make the most out of the afternoon than by hopping on a cruise. The promenade often serves as the starting point for premium Danube river cruises, including themed cultural sailings and private charter experiences that glide past Linz’s architectural landmarks.

Ars Electronica Center

Follow the Danube as it widens and brightens. Glass begins to outnumber stone. A short five-minute walk along the Donaulände leads straight to a building that looks like it already knows what tomorrow is doing.

The Ars Electronica Center is Linz at its most forward-thinking. Since opening in 1996, this “Museum of the Future” has explored how technology, science and art collide, cooperate and occasionally argue. Artificial intelligence, robotics, digital biology and interactive media take center stage, not as distant theories but as experiences meant to be tested and questioned. The architecture reinforces the message. Transparent by day and glowing electric blue after dark, the building turns innovation into a public spectacle on the riverbank.

Visitors who want structure with substance can join the Highlights Tour, available daily from Tuesday to Sunday at 11:00 AM to 12:00 noon and 3:00 PM to 4:00 PM. These guided experiences focus on artificial intelligence and the evolving relationship between humans and machines, presented through multiple perspectives. For something more tailored, guided tours on request include “Arbeitsplätze, fertig, los!” which explores future careers through hands-on technology and “Playing, Being… Experiencing Anton”, an immersive sound journey dedicated to Anton Bruckner. Group highlight tours and senior-focused tours are also available, allowing the content to adapt to pace and interest.

Evening: Wallfahrtsbasilika Sieben Schmerzen Mariae

A short ride up Pöstlingberg lifts the itinerary from urban rhythm to something more contemplative, with Linz quietly unfolding below.

Crowning the hilltop, the Wallfahrtsbasilika Sieben Schmerzen Mariae has watched over Linz since the 18th century. This baroque pilgrimage church, dedicated to the Seven Sorrows of Mary, was built between 1742 and 1748 and quickly became one of Upper Austria’s most important places of devotion. The facade is elegant rather than overpowering. Inside, soft light, gilded altars and restrained ornamentation create an atmosphere that feels reflective rather than theatrical. The basilica was designed for pause. Even non-pilgrims tend to slow down here.

Grottenbahn Pöstlingberg

Just steps away from the basilica, the atmosphere pivots from pilgrimage to playful in under two minutes.

The Grottenbahn has been charming visitors since 1906, originally built as part of the Pöstlingberg experience and designed to delight rather than impress. This fairytale attraction winds through illuminated grottoes filled with miniature scenes inspired by Austrian folklore, mythology and classic storybook characters. It may look lighthearted on the surface, but its longevity makes it a cultural artifact in its own right. For generations of locals, this has been a rite of passage. For visitors, it’s a reminder that Upper Austria knows how to balance depth with delight.

Evening visits feel especially charming when crowds thin and the illuminated scenes glow more theatrically. Ending the day here works because it breaks expectations. After art, power and devotion, Linz signs off with a wink.

Day 1 - Linz Tour Map

Day 2 - Mauthausen, Abbeys & Enns

Morning:

Mauthausen Memorial

This morning does not open lightly; it opens honestly. The city recedes, roads grow quieter and the tone deliberately shifts. About 25 minutes east of Linz, the landscape flattens, conversation softens and history takes the lead.

The Mauthausen Memorial occupies the grounds of one of the largest and most brutal concentration camp complexes of the Nazi regime. Established in 1938, Mauthausen and its network of subcamps were classified as Category III camps, reserved for prisoners considered “incorrigible” by the regime. In practice, this meant systematic extermination through forced labor. More than 190,000 people from over 40 nations were imprisoned here and at least 90,000 lost their lives. The location was strategic. Today, the memorial preserves key structures including the camp gate, roll-call square, prison barracks, crematorium, quarry and the Stairs of Death, alongside international memorials erected by former prisoner nations.

Wiener Graben

Now it’s time to descend from the main camp area straight into the physical heart of the system.

The Mauthausen Quarry, known as Wiener Graben, was the reason the camp existed where it did. This granite quarry fueled Nazi construction projects across the Reich and became the primary instrument of extermination through forced labor. Prisoners were driven down into the pit and forced to haul massive stone blocks upward, often weighing more than 40 kilograms, under constant brutality. The infamous 186-step staircase, later called the Stairs of Death, is still visible today. Many prisoners collapsed here from exhaustion, malnutrition or beatings. Others were deliberately pushed. The quarry was not a side operation. It was central to the camp’s function and cruelty. Visiting the quarry first grounds everything that follows. It explains the camp’s logic without words. The scale of the pit, the steepness of the climb and the exposure to the elements make the concept of “annihilation through labor” painfully clear.

Afternoon: St. Florian Monastery

A short southward drive of about fifteen minutes carries the afternoon away from confrontation and toward contemplation.

St. Florian Monastery is one of the most important Baroque monastic complexes in Austria and a long-standing intellectual and spiritual anchor of Upper Austria. Founded in the 11th century and rebuilt in grand Baroque form during the 17th and 18th centuries, the abbey is defined by balance, symmetry and restraint. The vast courtyards open slowly, leading to the Basilica of St. Florian, where marble, frescoes and gilded altars work in quiet harmony. Beneath the basilica lies the tomb of Anton Bruckner, placed directly under the great organ he once played, a detail that turns architecture into biography. The monastery also houses an extraordinary Imperial Library, with thousands of manuscripts and early printed works, as well as ceremonial halls that once hosted emperors and scholars. This was never just a religious site. It functioned as a center of learning, music and governance for centuries.

Kremsmünster Abbey

Monastery hopping mode: officially on. After the calm geometry of St. Florian, the route continues deeper into Upper Austria’s intellectual backbone. Rolling countryside replaces river flats, and after about a 40-minute drive south, another monumental abbey rises into view.

Kremsmünster Abbey, founded in 777, is one of the oldest Benedictine monasteries in Austria and a heavyweight in both faith and scholarship. While its baroque abbey church delivers the expected grandeur, the real surprise is how far ahead of its time this place was. The monastery became a center for science, education and research long before that was fashionable.

Its most distinctive feature, the Mathematical Tower, functioned as an early scientific observatory where monks studied astronomy, meteorology and mathematics centuries ago. Faith and reason were never in competition here. They shared the same address. The abbey complex also includes an exceptional library housing tens of thousands of volumes, medieval manuscripts and early printed works.

Evening: Enns Old Town

The day winds down without losing its spine. Monasteries give way to merchant streets. The road straightens, the pace loosens and after about a 25-minute drive north, Upper Austria’s oldest town takes the evening shift.

Enns is officially the oldest town in Austria, granted city rights in 1212, but its story starts much earlier as the Roman settlement of Lauriacum. This was a strategic Danube hub, first for legions and later for medieval trade. Today, Enns Old Town feels intimate and lived-in, with pastel façades arcaded courtyards and cobblestone streets that still follow their original layout.

And if you want to get the most out of the city, Enns often comes in the form of private Old Town walking tours, focusing on Roman archaeology, medieval urban planning and the evolution of Danube trade routes.

Stadtturm Enns

Save the climb for last. Evening settles in just as the town’s most recognizable landmark takes center stage.

The Stadtturm Enns, rising nearly 60 meters, has dominated the skyline since the 16th century, serving as a watchtower, fire lookout and symbol of Enns’ civic independence. Built during the Renaissance, it marks the moment when Enns fully stepped into its role as a self-governing town after centuries of Roman and medieval transformation. Inside, the structure reveals its layered purpose through staircases, chambers and historical exhibits that trace the town’s evolution from Lauriacum to modern Enns.

Day 2 - Mauthausen, Abbeys & Enns Tour Map

Day 3 - Bad Ischl, Hallstatt, Gosau, Dachstein

Morning: Bad Ischl

Imperial habits die hard, so even mornings here feel composed. The route turns south into the Salzkammergut, where mountains tighten the horizon and elegance starts to feel inherited rather than designed. After around 1 hour and 20 minutes of scenic driving, Bad Ischl makes its entrance quietly, like a place that has hosted emperors and sees no need to announce it.

Bad Ischl was the summer capital of the Habsburg Empire and it shows in the details. This was where Emperor Franz Joseph I spent decades escaping court politics, signing imperial decrees and proposing to Elisabeth, better known as Sisi. The town grew around spa culture and imperial leisure, fueled by salt wealth and Alpine air. Wide streets, refined villas and manicured parks still reflect that rhythm of seasonal grandeur. Bad Ischl never chased trends. It perfected consistency.

Kaiservilla

This is where the power clocked out for the summer.

A short, tree-lined stroll of about ten minutes eases away from the town center and into grounds that feel deliberately unhurried.

The Kaiservilla served as the summer residence of Emperor Franz Joseph I from 1853 until his death in 1916 and functioned as an informal seat of imperial decision-making. Originally built as a Biedermeier-style villa and later expanded, the residence reflects the emperor’s preference for simplicity over grandeur. Inside, rooms remain largely unchanged, including Franz Joseph’s study where he signed key documents of state, military orders and the 1914 declaration that led to the First World War. The villa also preserves deeply personal spaces connected to Empress Elisabeth, offering insight into private imperial life beyond portraits and legends.

Surrounding the residence is the Imperial Park, a carefully landscaped ensemble of meadows, tree-lined paths and sightlines designed for daily walks rather than display.

Afternoon: Hallstatt Old Town

The afternoon unfolds after about an hour’s drive deeper into the Salzkammergut. Hallstatt Old Town is one of Europe’s oldest continuously inhabited settlements, with a history shaped by salt long before tourism entered the chat.

This UNESCO World Heritage site grew rich from prehistoric salt mining, earning it influence centuries ahead of its size. The compact village unfolds vertically rather than outward, with pastel houses clinging to the mountainside and narrow lanes engineered by necessity, not aesthetics. At its core, Hallstatt balances fragility and endurance. Fires, landslides and time itself have tested it. The town adapted. Carefully.

Walking through the old town reveals layers rather than highlights. The market square anchors daily life. The lakeside axis frames the Evangelical Church spire against water and rock. And if you want a more immersive experience, Hallstatt is best approached through private guided village walks, often led by regional heritage specialists who focus on salt history, UNESCO preservation and how the town manages global attention without losing structural integrity.

Hallstatt Charnel House

Just a few minutes uphill from the lakeside heart of Hallstatt, the village reveals one of its most intimate traditions.

The Hallstatt Charnel House, located beside St. Michael’s Chapel, is a response to geography and faith working together. With limited burial space between the mountain and lake, the community developed a practice of exhuming remains after several years, carefully cleaning and preserving the skulls. Many were then hand-painted with floral motifs, names and dates, transforming remembrance into something deeply personal. Some skulls here date back to the 18th century. This is not a macabre spectacle. It is cultural pragmatism wrapped in ritual and respect.

What sets the Beinhaus apart is its quiet humanity. Each skull tells a story. Family lineage, local artistry and belief systems intersect in a space that feels more reflective than unsettling. The tradition also highlights how Hallstatt adapted to its physical constraints without losing dignity or meaning. Death here was never hidden. It was integrated into daily life.

Evangelische Pfarrkirche Hallstatt

A short walk from the Charnel House brings the itinerary to Hallstatt’s most iconic landmark, poised exactly where land and lake agree to share space.

The Evangelische Pfarrkirche Hallstatt, built in the 19th century, reflects the town’s strong Protestant heritage, a legacy tied to salt mining communities and their early embrace of the Reformation. Its slender spire rising directly from the lakeshore has become one of the most recognizable images in the Alps, but the church’s significance runs deeper than its postcard status. Inside, the atmosphere remains simple and restrained, aligning with Protestant values and allowing the setting itself to carry the emotion. The real drama unfolds outside, where water, village and mountain converge in perfect proportion.

Panoramic Viewpoint - Hallstatt Skywalk

Okay, perspective check. The village suddenly looks pocket-sized. The lake behaves like polished glass. And the mountains? Fully aware they’re carrying the scene. A smooth ride upward lifts the afternoon out of postcard mode and into full context, where Hallstatt finally reveals how tightly everything fits together.

The Hallstatt Skywalk, also known as the World Heritage Viewpoint, sits high above the village at roughly 360 meters above ground, delivering a clean, uninterrupted view of Hallstatt’s geography. From here, the logic of the place finally clicks. The tight cluster of houses. The narrow strip of land. The way the lake and mountains leave no room for excess.

Vorderer Gosausee

A scenic 20-minute drive from Hallstatt, climbing gently into the Dachstein foothills, delivers the kind of calm that cannot be rushed.

Vorderer Gosausee sits at the foot of the Dachstein Glacier, and it knows exactly what it’s doing. This alpine lake has long been a favorite of painters, mountaineers and anyone with an eye for composition. The water is famously clear, often mirror-still, reflecting jagged limestone peaks and dense pine forests with almost suspicious precision. Historically, the area played a role in regional forestry and alpine farming, but today its value lies in preservation and perspective. Nothing here competes for attention. Everything cooperates. Vorderer Gosausee is often included in private Salzkammergut nature and photography-focused tours, especially timed for late afternoon and early evening when the light softens and the crowds fade. These bespoke visits allow time for slow walking along the lakeside path, guided interpretation of the Dachstein massif and unhurried moments of stillness.

5 Fingers Viewing Platform

A final ascent into the Dachstein highlands brings the day to its most dramatic pause. The 5 Fingers Viewing Platform will be ending your third day in the region.

The 5 Fingers Viewing Platform stretches dramatically out from Mount Krippenstein, with five steel “fingers” projecting over open space high above the Dachstein landscape. One of the walkways features a glass floor, allowing a straight-down view into the void below, while the others offer solid footing for soaking in the panorama. From here, the views open wide across Hallstatt, Hallstättersee and the surrounding Alpine peaks, delivering one of the most cinematic lookout points in Upper Austria.

Set at over 2,000 meters above sea level, the platform is engineered to feel daring while remaining deliberately safe, with sturdy railings and clear sightlines that guide movement naturally. Its design encourages visitors to spread out rather than cluster, creating moments of quiet even during busy hours.

This stop closes the third day of your tour with a clean pause. After a full day of villages, lakes and layered history, the 5 Fingers delivers perspective in the most literal way possible.

Day 3 - Bad Ischl, Hallstatt, Gosau, Dachstein

Tour Map

Day 4 - Steyr

Morning: Stadtplatz Steyr

Last days deserve good pacing and even better settings.

Stadtplatz Steyr opens the final day on a strong note. This is one of Austria’s best-preserved medieval town squares, shaped by centuries of iron trade wealth and refined through Renaissance ambition. Patrician houses line the square in soft pastels, their façades decorated with ornate reliefs, wrought-iron signs and architectural details that reward slow looking. Steyr was once one of the most important industrial centers of Central Europe and this square was its civic living room.

Bummerlhaus

Now, a minute walk off Stadtplatz and suddenly Steyr is showing off its age in the best possible way.

The Bummerlhaus is one of the oldest surviving residential buildings in Austria, dating back to the 13th century, and it does not try to hide it. The name comes from the small snail sculpture fixed to the corner, a medieval house sign from the era before street numbers existed. Architecturally, this is Steyr’s Gothic standout. Pointed arches, mullioned windows and steep rooflines signal serious medieval wealth and long-term confidence. This was never just a home. It was a status update carved in stone.

What makes the Bummerlhaus especially compelling is how well it has held its ground. While the city evolved around it, the building kept its Gothic identity intact, offering a rare, street-level look at medieval urban life. It anchors Stadtplatz historically and visually, a reminder that Steyr’s success was built by merchants who invested in craftsmanship as much as commerce.

Afternoon: Schloss Lamberg

Five minutes on foot from Bummerlhaus and the scenery rewrites itself. Streets slope gently downward. Water starts to frame the story.

Schloss Lamberg occupies one of the most strategic locations in Upper Austria, sitting at the meeting point of the Enns and Steyr rivers. First established as a medieval fortress, the site evolved into a baroque palace under the Lamberg family, whose influence shaped Steyr’s political, economic and cultural life for generations. The architecture reflects that transition. Defensive foundations paired with ceremonial spaces. Strength softened by refinement. This was authority designed to be seen and understood.

The rivers are not a backdrop here. They are the reason the palace exists. Control of waterways meant control of trade, movement and power. Over time, Schloss Lamberg shifted from noble residence to administrative center, echoing Steyr’s own evolution from fortified town to industrial hub. The palace remains a hinge point in the city’s layout, quietly anchoring its past to its present.

Museum Arbeitswelt

Three minutes away from Schloss Lamberg and the narrative pivots again.

Museum Arbeitswelt sits in a former factory building, which already tells half the story. This museum tackles the social and economic history of work, industry and labor movements in Austria and beyond, with Steyr as its case study. Once a major center for iron production and manufacturing, the city shaped how modern labor systems evolved and how workers organized, resisted and adapted. The exhibitions connect industrialization, technology and social change without flattening the human cost. This is history with grit and relevance. Not distant. Not abstract.

What sets Museum Arbeitswelt apart is how deliberately inclusive and interactive the experience is. Target group-specific guided tours can be booked on request, including tours with sign language interpreters and visits led by staff trained in easy-to-read language, making complex themes accessible without dumbing them down. The museum also offers custom workshops for groups, supported by an experienced education team that adapts content to different interests and learning styles.

Evening: Pfarramt Steyr

Now it’s time to go uphill and witness the town exhale. Evening in Steyr prefers reflection over spectacle, and this stop understands that assignment.

Pfarramt Steyr is closely tied to the Stadtpfarrkirche St. Aegidius, serving as the administrative and communal heart of Steyr’s parish life for centuries. While modest in appearance, its significance runs deep. This is where civic faith, social care and daily rituals quietly intersect with the town’s public life. In medieval and early modern Steyr, the parish was not just a religious infrastructure. It was a social order, record keeper and moral anchor rolled into one.

Mündung der Steyr in die Enns

A short walk from Steyr’s historic core leads to the exact point where two rivers meet and the journey finds its natural full stop. Mündung der Steyr in die Enns marks the confluence that shaped Steyr’s destiny.

Long before palaces, factories or town squares, these rivers determined trade routes, settlement patterns and economic power. The Steyr brought iron and industry. The Enns carried goods outward to the Danube and beyond. Their meeting point explains why this city existed in the first place. Geography did the planning. History followed.

Standing here at the end of the tour feels intentional. After monasteries, imperial retreats, labor history and alpine drama, this stop strips everything back to fundamentals. Movement. Flow. Continuity. There’s no monument demanding attention, just water doing what it has always done, quietly and persistently.

Day 4 -

Steyr

Tour Map

Other Things to Do in Linz & Upper Austria

This is a region that opens up slowly. The longer one stays, the more it reveals. Linz and Upper Austria don’t rely on headline attractions or obvious luxury signals. Instead, they offer layered places that combine history, innovation, landscape and craft. These stops work best for travelers who enjoy substance, access and the feeling of discovering something before it gets over-explained.

- Nordico Stadtmuseum Linz: Nordico is where Linz explains itself without overselling. Housed in a former monastery, the museum focuses on the city’s social, cultural and photographic history, often through rotating exhibitions that feel contemporary rather than archival. It’s the kind of place that quietly reframes Linz from “industrial city” to layered urban narrative.

- Voestalpine Stahlwelt: This is industrial heritage done with precision and polish. Stahlwelt explores Linz’s transformation into a global center for advanced steel technology, using immersive design rather than static displays. The experience is surprisingly refined, focusing on innovation, sustainability and engineering excellence.

- Traunsee: Traunsee leans more dramatic, framed by steep mountains and sharper contrasts. Towns along its shore feel purposeful rather than ornamental. Luxury here comes through curated experiences such as private boat rides, scenic heritage routes and slow exploration of lakeside settlements.

- Steyrtalbahn: The Steyrtalbahn is nostalgia with structure. This historic narrow-gauge railway winds through alpine valleys and villages at a pace that forces attention outward. Vintage rail journeys here are often included in heritage-focused itineraries, appealing to travelers who value process over speed. It’s not about getting somewhere. It’s about watching Upper Austria unfold in chapters.

- Bad Ischl Congress & Theatre House: Bad Ischl’s cultural life didn’t end with the empire. The Congress & Theatre House continues the town’s tradition of intellectual and artistic gathering. Select performances and curated events are often woven into high-end Salzkammergut itineraries, adding a cultural layer to the spa-town narrative.

Things to Do With Kids in Linz & Upper Austria

Linz and Upper Austria don’t design children’s experiences as loud distractions. They design places that invite movement, curiosity and participation. Museums expect kids to touch and ask questions. Parks assume kids will run. Nature is left open rather than over-managed. That’s why family travel here feels balanced instead of exhausting.

- Grottenbahn Pöstlingberg: A small train pulls into glowing caves filled with fairy-tale scenes inspired by Austrian folklore. The experience is short, immersive and delightfully old-school, which works in its favor. There are no flashing screens or loud sound effects. Just whimsy, imagination and charm that hold attention without overstimulation.

- Zoo Linz: Built into the hillside of Pöstlingberg, Linz Zoo keeps things manageable. The layout is compact, paths are shaded and animal enclosures feel approachable rather than sprawling. The focus on European wildlife and farm animals makes it easy for kids to connect what they see to the world around them.

- Donaupark Urfahr: Donaupark is Linz’s built-in reset button. Wide green spaces stretch along the river, offering room to run, cycle, picnic or simply sit without pressure. For kids, it’s freedom. For adults, it’s relief.

- Aquapulco Piratenwelt: When energy needs an outlet, Aquapulco delivers. This pirate-themed water world is built entirely around kids, with slides, splash zones and wave pools designed for different age groups. It’s structured, supervised and energetic without feeling chaotic. Ideal for a dedicated fun day when museums are off the table.

- EurothermenResort Bad Schallerbach: What makes this resort family-friendly is smart separation. Kids get their own splash zones. Adults get calmer spaces. Everyone enjoys the same place without stepping on each other’s vibe. Thoughtful design wins.

- Nationalpark Kalkalpen: This is outdoor time without pressure. Guided family walks focus on spotting animals, understanding forests and noticing details kids usually miss. It’s calm, uncrowded and refreshingly real. Perfect for curious kids who like asking “what’s that?” every five minutes.

Day Trips From Linz & Upper Austria

Day trips around Linz and Upper Austria are dangerously easy. Like, “why is everything this good and this close?” easy. One smooth ride and suddenly you’re standing in a UNESCO old town, an imperial spa where emperors summered or a lakeside so clear it feels edited. No suitcase drama. No overplanning spiral. Just clean, satisfying escapes that slide perfectly into a single day. These day trips aren’t filler. They’re the kind that make you feel like you planned really well, even if you didn’t overthink it.

- Salzburg: A smooth 1 hour and 15 minutes from Linz is all it takes to land in one of Europe’s most layered UNESCO cities. Salzburg’s Old Town stretches elegantly along the Salzach River, framed by baroque landmarks like Residenzplatz, Salzburg Cathedral, and the cliff-top Hohensalzburg Fortress looming above it all. Beyond the obvious icons, the city rewards wandering through quieter lanes, cathedral courtyards and elevated viewpoints that reveal how power, religion, and music shaped its layout.

- Hallstatt: At roughly 1 hour and 30 minutes from Linz, Hallstatt feels far more remote than it actually is. This UNESCO World Heritage village is built on a razor-thin strip of land between lake and mountain, shaped almost entirely by prehistoric salt mining. The Old Town, lakeside axis with the Evangelical Church, and steep, compact streets explain how geography dictated every design choice.

- Attersee: A calm 1 hour and 15 minutes from Linz, you arrive in Attersee, known for its exceptionally clear waters and artistic legacy linked to Gustav Klimt. Shoreline towns, open vistas, and unobstructed lake views create a sense of visual calm that contrasts with busier alpine destinations.

- Passau: Passau makes an easy cross-border day trip, with the drive from Linz taking just under an hour and a half. Known as the City of Three Rivers, this Bavarian town sits at the dramatic meeting point of the Danube, Inn and Ilz. The Old Town is compact but rich, centered on Dom St. Stephan, home to one of the world’s largest cathedral organs and surrounded by baroque streets influenced by Italian master builders.

- St. Wolfgang: St. Wolfgang sits right at the edge of a comfortable day-trip distance, reached in about an hour and a half from Linz. The village grew around the Pilgrimage Church of St. Wolfgang, home to the famous Pacher Altar, and still carries the rhythm of a historic religious hub.

Golf Courses in Linz & Upper Austria

Golf in Linz and Upper Austria doesn’t come with flashy clubhouses or loud prestige moves and that’s exactly why it works. This is golf that fits the rhythm of the region: quiet confidence, strong landscapes, and courses that care more about flow than flexing. Courses are close enough to Linz to fit into a half day, yet scenic enough to feel like a proper escape. Expect parkland layouts, forest-framed fairways, subtle elevation changes and greens that reward thinking instead of brute force. Here are some of the best spots to tee off in Linz and Upper Austria.

- Golf Club Linz St. Florian: A quick drive from Linz city center, this course blends accessibility with design that keeps both beginners and experienced players engaged. Set in gently rolling terrain, the layout feels open and thoughtful, with well-kept fairways framed by mature trees. It’s one of the closest options to Linz proper.

- Golf Club Schlossberg: Located north of Linz near Freistadt, Schlossberg is known for its strategic routing and scenic parkland. The fairways wind through subtle elevation changes and offer water features that reward careful shot placement. There’s a classic Austrian countryside feel here. It is balanced, serene and satisfying. The course pairs well with bespoke golf packages that include GPS cart upgrades and priority tee times, perfect for travelers who don’t want to wait to play.

- Golfpark Böhmerwald: Positioned closer to the Bavarian border, Böhmerwald sits in forested uplands that make each hole feel slightly more secluded. The terrain is rolling but gentle, with a mix of strategic water hazards and tree lines that shape play. It’s a great choice if you want golf that feels deeply tied to nature. What makes this place stand out is how the club offers custom cart routing services and advanced course briefings that help visitors read greens and plan strategy in advance.

Race Courses in Linz & Upper Austria

This is a region where horses are woven into daily life, sport and history, not staged for spectacle. The energy here is less champagne-and-hats, more polished boots and serious horsemanship. And honestly, that makes it far more interesting. Instead of classic racecourses, the cities offer an equestrian venue that feels lived-in and purposeful. It’s the kind of scene that rewards curiosity. You don’t just watch from afar. You understand how the sport fits into the rhythm of the place.

- Reitpark Gstöttner: At the edge of the Mühlviertler Alm region, Reitpark Gstöttner brings horses into sweeping Austrian highland scenery. The riding park isn’t a traditional racetrack, but it is a full-on equestrian hub with dressage arenas, jumping areas, trail riding networks and bridle paths that feed into 680 km of tagged routes across forests, brooks and pastures. This place fits perfectly into a high-end equestrian day trip: think private guided trail rides, tailored lessons, and even riding vacations.

Michelin-Starred Restaurants in Linz & Upper

Austria

This part of Austria isn’t trying to mimic Paris or Vienna. Instead, it channels modern technique through local ingredients, lakeside inspirations and a quiet confidence that only long tradition can give you. You’ll find a mix of creative fine dining, nature-driven tasting menus and beautifully executed contemporary cuisine. And yes, these are places you plan your evening around, not accidentally stroll into.

- Rossbarth: Rossbarth reads like a manifesto on simplicity and zing. With one Michelin star to its name, this restaurant strips back noise and focuses on ingredient integrity and seasonal creativity. Think dishes where wild-caught saltwater fish meet rich autumnal vegetables and subtle uses of smoke and acid to frame every bite. The setting, a vaulted historic room with a small kitchen window you can peek through, tells you right away this is about craft, not flash.

- Verdi: Verdi’s Michelin star reflects both impeccable technique and personality in the plate. Close to Linz’s cultural heart, it’s where presentation feels alive. Renowned chef Erich Lukas (whose family lineage in Linz kitchens goes way back) ensures every menu feels like a conversation rather than a checklist.

- RAU nature based cuisine: Out in Großraming, RAU lives up to its name: nature-based cuisine that doesn’t flirt with trends but merges wild landscapes with deft technique. Michelin awarded RAU both a star and a Green Star for sustainability. It is a badge that signals dishes are as thoughtfully sourced as they are delicious. Here, the woods and fields aren’t backdrops; they’re partners in the plate, translated through artful, introspective presentations that elevate local game, herbs and foraged elements.

- Paula: Tucked into the storybook village of St. Wolfgang, Paula stands as a star-making example of creative Austrian cuisine with French echoes and a soul. Michelin lists it as a One-Star restaurant for high-quality cooking and the tasting menus, often six to eight courses featuring seasonal alpine fish, heritage produce and thoughtful wine pairings, lean into pure flavors with elegant restraint.

- Restaurant Lukas Kapeller: Steyr’s Michelin destination blends modern technique with regional reverence. Lukas Kapeller (chef/owner) balances playful twists and structured precision, often pairing unexpected elements. The ambiance mixes local warmth with minimal elegance, making it perfect for a celebratory dinner that still feels genuinely Austrian at heart.

- Tanglberg: In Vorchdorf, Tanglberg delivers French-leaning haute cuisine rooted in local supply and seasonality. Michelin’s nod here signals refined technique and classic sensibilities. The gallery-style space elevates the meal to a multi-sensory experience, not just eating.

Where to Eat in Linz & Upper Austria

Linz and Upper Austria don’t do try-hard dining and honestly, that’s the flex. This is a food scene that knows its worth: hilltop restaurants with main-character views, lakeside spots made for long lunches that accidentally turn into dinner, and city kitchens that balance craft with cool. Think confident flavors, zero filler, and places that feel less “special occasion only” and more this is exactly where you should be eating right now. Here are some local restaurants that you should visit.

- Pöstlingberg Schlössl: Perched high above the city, this is where Linz dresses up for dinner. The approach alone, winding uphill toward the Pöstlingberg, sets the tone. Inside, refined Austrian cooking meets old-world elegance. This is where milestones are celebrated and sunsets quietly steal the show.

- Schmankerl Steyr: If Upper Austria had a culinary love language, this would be it. Schmankerl Steyr leans into comfort without cutting corners. Just think of regional dishes, generous portions and flavors that feel rooted rather than rehearsed.

- Restaurant Essig’s: This is where restraint becomes a flex. Clean lines, focused menus and thoughtful plating define Essig’s approach, making every dish feel intentional. The cooking favors balance over bravado, allowing seasonal ingredients to speak clearly. Quietly confident, this is one of Linz’s most polished dining rooms.

- Speisekammer am See: Lake air, relaxed pacing, and a menu that reads like a love letter to the Salzkammergut. Speisekammer am See thrives on its setting. It’s the kind of place where lunch stretches into late afternoon without resistance.

- ÄNGUS Steaks & Izakaya: Two worlds, one table. ÄNGUS pairs premium steakhouse confidence with Japanese izakaya flair, creating a menu that jumps effortlessly from expertly grilled beef to precise small plates. The atmosphere leans urban and energetic.

- Taborturm: Dining inside a medieval tower sounds dramatic because it is. Thick stone walls, sweeping Danube views, and a menu that blends Austrian classics with refined, modern touches make this feel like a time-travel dinner done right. It’s atmospheric without being gimmicky.

Where to Drink in Linz & Upper Austria

Nights here aren’t about velvet ropes or forced hype, they’re about finding the right room for the right mood. From DJ-driven dance floors to pubs that feel like a second living room, the scene thrives on personality over polish. These are the places locals default to, students swear by, and visitors accidentally stay out too late in.

- Lennox: This is where Linz goes when the night needs energy, fast. Lennox thrives on DJ-driven nights, crowded dance floors, and a crowd that didn’t come to stand still. What makes it stand out is consistency: when people want a proper club night without guessing the vibe, this is the default answer.

- The Irish: Reliable in the best way possible. The Irish stands out because it never overthinks things. Here you can have solid pints, familiar music and a crowd that’s open, social, and easy to blend into.

- Helmut: Helmut plays the long game. Clean interiors, strong cocktails and a creative crowd give it an edge that feels intentional but not exclusive. What sets it apart is its calm confidence. This is where people go when they want atmosphere without noise and style without trying too hard.

- Coconut Beachbar: Summer energy bottled and served. Coconut Beachbar stands out for one reason: it doesn’t feel like Upper Austria at all, in the best way. Sand underfoot, sunset views, and laid-back drinks turn regular evenings into something that feels suspiciously like a holiday.

- Red Rooster: Red Rooster knows exactly what it is and doesn’t apologize for it. Loud music, busy nights, and a party-forward crowd make this one of Linz’s most unapologetically fun spots. It stands out by committing fully to chaos and pulling it off.

- Das Goldene Einhorn: Das Goldene Einhorn offers the opposite of rush. With a cozy interior and an easygoing crowd, it’s built for lingering conversations and unplanned late nights. What makes it stand out is comfort. Here, nothing feels forced and no one’s watching the clock. It’s the kind of place where “one last drink” quietly becomes the final chapter of the night.

Cafes in Linz & Upper Austria

Cafe culture here isn’t about rushing caffeine, it’s about mood, ritual and choosing a place that matches the pace of the day. Some cafes are made for deep conversations and lingering glances out the window. Others are quick resets between plans or creative hideouts where time stretches without asking permission. These spots stand out not just for what’s in the cup, but for how they make the hours feel lighter.

- Rahofer: Steyr’s cozy classic with a local reputation. A beloved café/restaurant hybrid with a warm ambiance that feels like an easygoing home base in the heart of town. It has friendly service, hearty staples and strong coffee are part of the draw.

- Teesalon Madame Wu: This spot pairs delicate teaware and interiors with a lighter café menu. Some visitors rave about the serene setting and the chance to unwind with tea flights. Teesalon Madame Wu is also highly regarded for its extensive tea selection and elegant presentation. So if you are looking for a spot for long conversations, quiet breaks or solo afternoons that don’t need a schedule, this is the place for you.

- Friedlieb und Töchter: Consistently rated among Linz’s top cafés, Friedlieb und Töchter is loved for its beautiful pastries and polished yet cozy atmosphere. This place is known for the quality of the coffee and the attention to detail in every slice of cake. It’s a natural choice for catch-ups that deserve something sweet.

- Kuchltheater Bad Ischl: Kuchltheater feels like a café with a personality and that’s exactly why people love it. Reviews frequently mention the creative pastries, charming interior and comforting menu that goes beyond just coffee. It’s a place that turns a simple café visit into a small experience, especially in the heart of Bad Ischl.

- Gerberei: This spot is known for its relaxed, light-filled setting and strong focus on quality coffee. If you want to visit a cafe that is effortlessly inviting, then you might want to drop by Gerberei. The riverside location adds to its appeal, giving every visit a calm, unforced rhythm.

Where to Stay in Linz & Upper Austria

- Rosewood Schloss Fuschl (5 stars): This is alpine luxury at its most cinematic. Rosewood Schloss Fuschl is known for its fairytale setting on Lake Fuschl, where historic castle architecture meets modern, ultra-polished hospitality. What makes it stand out is the sense of total escape with private lakeside moments, refined dining and interiors that feel timeless rather than trendy. It’s the kind of place chosen when the stay itself is the headline.

- Hotel Seevilla Wolfgangsee (5 stars): Seevilla is all about lakeside intimacy. Overlooking Wolfgangsee, this hotel is known for its serene atmosphere, direct water access and views that quietly steal attention from everything else. This hotel is elegant without being overwhelming, peaceful without feeling isolated. Ideal for travelers who want luxury that leans calm rather than ceremonial.

- Hotel Am Domplatz (4 stars): Hotel am Domplatz delivers refined city luxury with zero noise. Located beside Linz’s New Cathedral, it’s known for its minimalist design, soundproofed rooms and tranquil atmosphere despite being right in the center. Everything feels deliberate, from the architecture to the service, creating a stay that feels quietly elevated and deeply comfortable.

- ARCOTEL Nike (4 stars): ARCOTEL Nike is instantly recognizable for its Danube-facing position. Known for spacious rooms and river views, it offers a sense of openness that’s rare in city hotels. The location bridges culture and calm, with Ars Electronica and the Old Town within walking distance.

- Leonardo Boutique Hotel Linz City Center (3 stars): This hotel nails the modern city stay. Leonardo Boutique is known for its central location, clean-lined design and smart use of space, making it especially popular with younger travelers and short-stay visitors. This hotel has a personality. It has stylish rooms, a relaxed vibe and everything important just steps away.

Best Time to Visit Linz & Upper Austria

If Linz and Upper Austria had a “this is it” moment, this would be it. Late spring to early summer is when the region hits its sweet spot. It is energetic but not crowded, polished but still relaxed. Think longer days, cafe tables spilling onto sidewalks and the Danube finally stepping into its main-character era. To borrow from Dead Poets Society: “No matter what anybody tells you, words and ideas can change the world.” Around here, that translates to cities and landscapes that feel fully awake.

During May and June, Linz is fully in its glow-up era. The city moves like it knows it looks good. The Danube starts serving soft golden light, cafe terraces stay booked for all the right reasons and suddenly every walk feels like accidental content. Museums turn into aesthetic pit stops, brunch runs long and next thing you know it’s aperitivo o’clock. It’s warm enough for outfit planning, cool enough to keep things effortless, and just busy enough to feel alive without crowding the frame. And for Instagram? Prime time. Think river reflections, pastel skies, and streets that don’t need a filter.

Beyond the city, Upper Austria feels open and inviting. Lakes reflect soft early-summer light, alpine towns ease into their rhythm and day trips actually feel like an upgrade, not a logistical challenge. It’s the kind of season where itineraries breathe. Nothing rushed, nothing forced, everything landing exactly where it should.

This is peak Linz energy: good weather, good pacing, and a destination that doesn’t miss.

Festivals in Linz & Upper Austria

- Ars Electronica Festival: Taking place every September, this is Linz’s global mic-drop moment. Ars Electronica transforms the city into a living lab where art, technology, science and society collide. Installations pop up across museums, universities and public spaces, drawing creators and thinkers from around the world.

- Ulrichsberger Kaleidophon: Held in late April, this intimate music festival in Upper Austria’s Mühlviertel region is all about curiosity. Kaleidophon brings together jazz, improvised music and experimental sounds, with genre-blurring performances in a setting that feels intentionally off the mainstream path.

- Pflasterspektakel: Late July is when Linz hands its streets over to performers. Pflasterspektakel is one of Europe’s largest street art festivals, filling the city center with acrobats, musicians and unexpected moments around every corner. It’s loud, colorful, and joyfully chaotic.

- Musikfestival Steyr: Spanning July and August, this open-air music festival uses Steyr’s historic old town as its stage. Operas, operettas and musical performances unfold against medieval backdrops, blending high culture with summer-night atmosphere. It’s elegant without feeling stiff, making it especially appealing for travelers who want culture served with fresh air and ambiance.

- Brucknerfest: Taking place from September into October, Brucknerfest is Linz’s classical heavyweight. Dedicated to composer Anton Bruckner, the festival features orchestras, soloists and ensembles from across Europe. Concerts are held in venues like the Brucknerhaus.

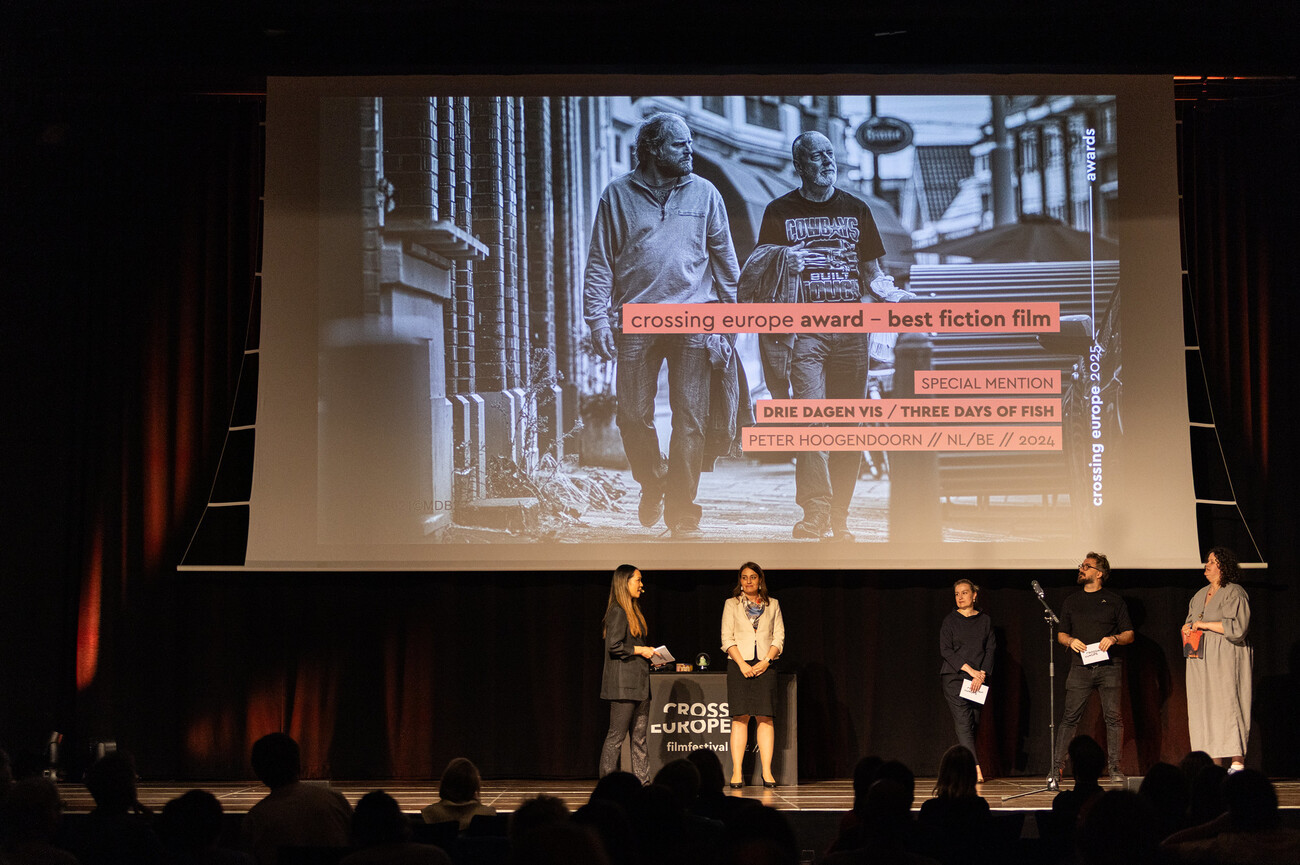

- Crossing Europe Film Festival: Arriving in April, Crossing Europe kicks off the cultural year with sharp storytelling and strong perspectives. The festival focuses on European cinema, spotlighting independent films, emerging directors and bold narratives. Screenings, talks and events take over the city, giving Linz a creative buzz just as spring begins to settle in.

Let us know what you love, where you want to go, and we’ll design a one-of-a-kind adventure you’ll never forget.

Get in touch

Miriam

Europe & Africa Expert

Romina

Europe & Africa Expert

Laura

Europe & Africa Expert

Our offices: